When I browse sites like UpWork or Thumbtack, I see countless people wanting to turn their ideas or manuscripts into books. But often, their listings are so off-base for what the industry-standards are that they can find it hard to actually get any interested freelancers to apply to their project. Even more problematic are the authors who jump into creating a book 100% themselves without any publishing experience. They often make key mistakes that can make their book seem more amateurish than it needs to.

Here are the biggest mistakes I see that can really make an indie book look unpolished.

1. Thinking an editor is a formatter

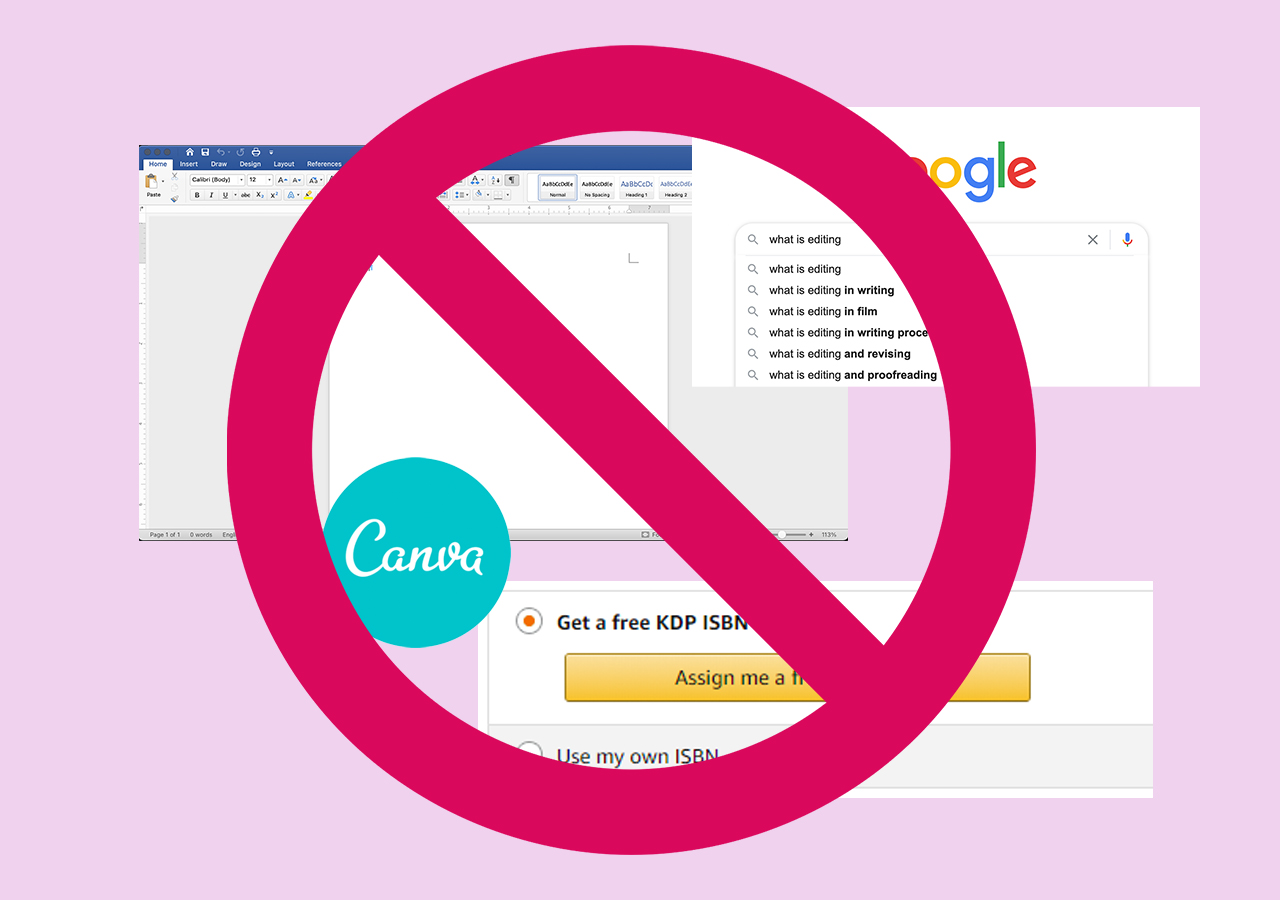

Editing a book is a completely different skill than doing the internal formatting for a book. Too often, I’ll see people on UpWork looking to hire an editor-cum-formatter, not realizing that one is well-versed in editorial practices and then other in graphic design.

You can occasionally get people who do both (I count myself among them), but generally, the interior formatting work of someone who edits and formats is most suited to books that are going on KDP or Smashwords because the all-in-one process will usually be through Word, Google Docs, or Pages. If you’re looking for someone who is an expert at InDesign (the industry-standard for traditionally-published books), chance are they’ll be a dedicated graphic design professional.

2. Not understanding the different types of editing

If you’ve visited my Services page, you’ll notice terms like “proofreading,” “line editing,” and “developmental editing.” Unbeknownst to many authors looking to self-publish, there are different types of editing, which each focus on different aspects of the text.

I break it down like this:

- Copyediting – in-depth editing focusing on grammar, syntax, consistency, and fact-checking

- Line Editing – in-depth editing at the line and paragraph level that focuses on language, style, redundancies, clarity, etc.

- Developmental Editing – high-level editing concerned with plot, characterization, marketability, flow, overall tone and style

If you want more details about the differences, Scribe media has created a great guide to editing.

Most books (and publications more generally) will need every type of editing. Sometimes editors can combine them into one round of editing (usually for proofreading and line editing) using Track Changes. But, usually, your book with need at least three rounds of professional editing to target all three different types of editing.

I do recognize that this is not always feasible monetarily for indie authors and publishers. If you are unable to pay for a full developmental edit, for example, you should at least make sure you have beta readers who are able to give you feedback on the plot, characters, and continuity of the book. The more eyes the better before the ARC goes out, or else you’ll end up getting reviews that mention errors in your books.

3. Only having a DOC/DOCX and PDF of your book.

If you want to do any type of media, blogger, or library outreach, you’ll likely need an EPUB of your book. In fact, I highly recommend that you have five versions of your book:

- a “clean,” unformatted DOC that’s proofread

- a MOBI

- an EPUB

- a PDF (generally for use in the printed book)

- and a “source file” of your book from whatever formatting software you or your professional use (including InDesign and Vellum).

Did you know: both Google Docs and Pages can export directly to EPUB format?

If you’re using only Word to format your manuscript into a book, I highly recommend using a site or program like Smashwords or Calibre to convert your book to other formats.

These formats will not only be useful when you go to upload your manuscript to your printer or distributor, like KDP, but they’re a near-must to use reviewer sites like NetGalley and Booksprout.

4. Misunderstanding how KDP-assigned ISBNs and Distribution work

In an effort to save money on their ISBNs, many self-published authors use the free KDP or IngramSpark-assigned ISBN. This can seem like a good idea, particularly if you’re just looking to sell on Amazon. But using a free ISBN can hurt your book in a few ways:

1. Distribution delay

It will take months for your book to show up on bookstores websites, if they do at all. Amazon’s extended distribution options is very slow to update metadata. What that means is that, if you’re looking for your book to be available at Barnes & Noble the very second it’s your publication date, you’re out of luck. It usually takes about three months to show up on sites like B&N.com, Bookshop, and IndieBound, if they show up at all.

2. Misleading “extended” distribution

KDP extended distribution won’t guarantee brick-and-mortar book placement. While your books will eventually show up on B&N.com, there is no guarantee the Powers-That-Be will stock it in stores, nor that it will appear on any other book retailer site (aside from B&N and Amazon).

3. Library Issues

Furthermore, this distribution makes it hard for libraries to order your book. If you’re trying to do events, most libraries won’t be able to order your books for a few months. While KDP extended distribution and the free ISBN do eventually get your book into the Ingram catalog, the delay means that if you’re trying to do pre-press PR, it will seem like your book doesn’t exist, from the perspective of librarians. That’s because they won’t be able to find it in their distributor catalogs and therefore won’t be able to order a library copy.

4. Missed marketing opportunity

You will miss out on an opportunity to fully claim your book. When you create a KDP ebook, you have the chance to add an imprint name. There, you can use your DBA name or your author LLC. However, for paperbacks that use a free ISBN, there is no such option. Instead, a book will show up just as “independently published.”

5. Allows people to profile your book as “poor quality”

Even if you don’t want the additional marketing ability of a custom imprint metadatum, you’ll be sacrificing some legitimacy if your book is independently published. Unfortunately, the publishing industry can be very elitist. Bookstores and libraries may not want to stock a book that says “independently published,” even if they’re technically able to. Part of this apparent bias is actually due to the fact that if you are unwilling or unable to pay for a $100 ISBN, then chances are you’re also unwilling or unable to pay for professional editing, formatting, and cover design. That may not be true, but for bookstores, libraries, and media outlets who receive thousands of requests a month (if not more), it’s an easy way to weed through the bunch.

If you use a custom ISBN—which, in the US, you must get via Bowker—your book will show up sooner in the Ingram (or whichever distributor you’ve chosen) catalog, and thus sooner on bookstore websites. This means your pitches can work the month of release because bookstores and libraries can order your book immediately.

5. Designing a book cover with free stock photos

While there are authors who are savvy-enough at design to create successful covers themselves, I highly recommend hiring a designer if you have no graphic design or illustration experience. You can also use a premade cover design from a professional for a lower cost.

With that said, if you are designing your own cover, you should know the rules for photo licensing. (If you hire a designer, you’ll still need to follow these rules. However, a reputable designer should guide you through them.)

What do I mean by this?

Many “free” stock photo websites, like Pexels, have certain terms for their photos. Sometimes you need to give an attribution; sometimes not. What can become a problem is all the instances in which a free stock photo site is actually using copyrighted materials, or when you’re not the actual licensee (e.g. using free Canva stock).

Did you know: You likely shouldn’t use free Canva images or designs.

And, in no situation should you just search in Google and grab images from there. Google advanced search does allow you to narrow your enquiry by licensing, but you can still run into issues there if one site has taken a photo from another and then marked it as “free for use” when the original was not.

Your safest bet is using a photograph from a well-known stock photo site like Getty Images, Deposit Photos, or Shutterstock.

Oh, and if you’re wanting to sell merch of your book cover (say, bookmarks with your cover on them), you may need to get an extended license. The rules vary by content creator and by content, so be sure to check every time.

* * *

Were these tips helpful? Do you have any to add? Comment below!